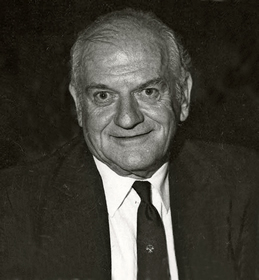

John Levy (1921-2005)

Tribute by David Dickinson

John Levy was born in Brazil where he contracted polio when he was 18 months old, and his mother brought him back home to Cornwall. John’s love of Cornwall was pivotal to him and his family and was key to the initiation of his research career.

John later had his left leg, damaged by the polio, amputated and a false leg fitted. That, along with his stick was his trademark. He spent his undergraduate years as a cox for the Imperial College rowing crews. His booming voice on the river was famous, as it was in the lecture theatre. John told me that when he took his false leg off while coxing in races, people sometimes jokingly accused him of cheating by reducing his weight. His involvement in rowing stayed with him throughout his life.

During his time at Imperial, he registered for a research project which involved growing and studying diseases of tomatoes, a fruit which I later learnt he couldn't eat.

In my early years at Imperial College, we always had lunch together in his famous room. My job was to purchase a cheese sandwich and of course his favorite Cornish pasty from the student bar. The first thing he would do would be to remove any trace of tomatoes from the sandwich. So many of our ideas were formulated over those lunches.

Early in John’s PhD studies his career changed. The department was asked to contribute to an MSc course on timber engineering being run by Geoffrey Booth in the engineering department. John was asked if he could fill that role and he switched to teaching wood structure, wood decay and preservation in this long running and highly successful MSc programme. John also taught plant anatomy in the Botany department at Imperial, and developed his own highly popular timber technology option in the department.

Because John never finished his research in Plant Pathology he remained Mr. Levy until he was awarded a Doctor of Science and became Professor of Wood Science in 1981. He was later awarded the prestigious Fellowship of Imperial College.

Having established his teaching career he was very keen to develop his research interests. Remarkably John was able to combine his love of Cornwall with a research opportunity.

At that time the Royal School of Mines at Imperial College owned a disused tin mine at Tywarnhale in Cornwall. Mining students were taught underground surveying and John was asked to survey for decay the hundreds of feet of vertical wooden-sided ladders which gave access to the different deep levels in the mine. John realised that this was an ideal test site for preservative treated timber in extreme conditions. He convinced the British Wood Preservation Association to install new ladder sides treated with existing and experimental preservatives. Over the years I spent many hours examining the ladders with John. In the low passages he lay on a ladder while we dragged him along.

This early work led to the establishment of a research group of worldwide renown, and it remains as his legacy.

At that time, the Princess Risborough laboratory was being encouraged to fund research at UK universities and several studentships and post-docs were funded including PhD studies by their own staff, including Tony Bravery and Janice Carey. Other studentships were funded by individual company members of the BWPA.

Key to these developments was the close relationship with John Savory and Professor Reginal Preston which led John to develop his work on the micro-morphology of decay.

His success did not go unrecognised in the department, and they decided he needed another full-time staff member to help with his section. It is here that I got the luckiest break of my career, John Savory encouraged John Levy to ask me to apply for the position. The rest is history that others will be aware of.

Later our Rector announced a scheme to recruit new staff in active research areas. If any group could raise industrial funding for at least 3 years for a new lecturer, then the College would continue the funding. That was gift to John. I believe it only took John a couple of days to sort out the initial support. That is how much respect the industry had for him. Eventually Richard Murphy was appointed to the new position.

John was a mentor and inspiration to many. There was a constant stream of students and staff in and out of John’s room. His passion for timber was contagious, and he was always eager to share his knowledge with students, colleagues, and professionals in the field. John’s legacy is not just in the papers he authored, it is also in the minds and hearts of those he inspired to think differently about their own capabilities and research.

John Levy's passing was a great loss to the scientific community and to all who knew him. However, I am convinced his contribution to timber technology and wood preservation will continue to influence and inspire others for generations to come, although it is now through those fortunate enough to have been influenced by John himself. We remember John not only for his remarkable achievements but also for his kindness and his unique way of encouraging young scientists and making people feel good about themselves : he was a fine human being.

A few memories dear to me:

When I first went to work in industry my boss sent me to spend time with people in the field. I remember entering that famous office, and then clearing the books from a chair to sit and being fascinated by him. I had a sample with me of a decaying piece of treated board from an above ground swimming pool. It was treated with CCA and sprayed to show the Cu distribution. Out came the sliding shelf from his ancient desk to reveal the only clear surface in his office. As we discussed the sample, he made copious notes, and I realised that I really could be interested in this subject.

I was also sent to The Princess Risborough Labs where I spent a lot of time with John Savory, and we got on so well. Little did I realise how important that relationship was to be for me in helping with my career with John Levy.

John once confided in me over a few glasses of sherry in his office, that he didn’t necessarily believe in an after-life. His belief was to be remembered for what one does. He certainly achieved that.

Finally, I will always remember speaking to Jean Taylor the entomologist who eventually moved to Protim. She spoke about John Levy and she described him as “simply a fine human being”. That stuck with me all the time I knew John.

David Dickinson

Tribute by Harry Greaves

I first met Professor John F Levy (JFL) in 1965 during my undergraduate work at the erstwhile Forest Products Research Laboratory in Princes Risborough.

I was studying the microfungi attacking treated stakes in FPRL’s field test site and methods for their isolation. John Savory was my supervising boss at FPRL and JFL, who had a good working relationship with the lab, visited us to discuss possible future research, along similar lines, in his laboratories at Imperial College.

He was a wonderful mentor to me as a young man starting out in a field so much dominated by the JFL approach and understanding. His knowledge of the field and network of key players in the UK wood preservation industry and in UK wood science academia was second to none. He was also one of life’s true gentlemen and proved highly instrumental in furthering my career – TRADA Bursar, Fulbright Scholar, post-doc researcher at NC State and, ultimately, employee at the CSIRO Division of Forest Products in Melbourne, Australia. These milestones in my career all had the JFL guiding hand.

I believe JFL has produced more researchers in the wood preservation and biodeterioration field than any other single great research leader. Indeed, without JFL postgraduates the IRG community (family) would be very much the poorer!

Harry Greaves

Tribute by Tony Bravery

I feel it is of FFI (“First-Class Fundamental Importance”) to acknowledge him in this way! An expression which will resonate with all who encountered John’s inimitable coaching!

I too would want to remind everyone of the occasion at the IRG Dinner at Ripon Castle in 1992, in the course of the Harrogate Meeting when I, (as Chairman of the UK Organising Committee – and as it happens, In-coming President)) gave a short presentation in which I invited all present who had spent time in study with John at Imperial College to stand up. As my memory serves me there were around 30 from all quarters of the world who responded. By way of acknowledgement I was then able to present him with a large volume on ‘Trees and Timber of the World’ we had organised, signed by pretty much all those who had stood up.

We would all remember an office where every shelf and every horizontal surface was covered pile-high with files, books, papers etc like some sort of waste paper store – but John knew where every item required of the moment had been ‘filed’! His indomitable spirit in travelling all over the world was an inspiration to even the most able-bodied of us all. His paternal approach and informality engendered a huge affection and gratitude for his care, guidance, encouragement, wisdom and comradeship. We all knew we were one of John’s ‘products’!

As a result of John’s close friendship with another ‘John’ (and giant of IRG ‘s early years - John Savory) I believe I was the first in quite a sequence of recruits to the then new PhD Student Scheme by which young scientists already working in research organisations could study part-time in the University towards their PhD. Another example of John’s unique enthusiasm and commitment to encouraging young people into the world of wood science.

He was a leader in a generation of Senior Academics and Industrial Scientists in Europe and indeed across the world, who put wood science generally and wood protection in particular, at the forefront of technical advances in the commercial world of practical and industrial wood product developments.

He leaves a huge legacy!

Tony Bravery

Tribute by James Coulson

I knew John Levy very well during the 1980's, when I re-launched the Tyne-Tees Branch of the Insititute of Wood Science in the UK, which had become dormant in the 1970's. I had first met John when I took my final Wood Science exams at Imperial College, London, in 1978; and he was both friendly and extremely knowledegable. When I invited him to come all the way to Newcastle-upon-Tyne from London (no mean feat, 40 years ago!), he readily agreed: and he brought with him lots of highly interesting coloured projector slides (remember them - in the days before PowerPoint?), with which to illustrate his erudite talks.

I still have clear memories of him always being in very good humour and with such an easy presentational manner. Following each Branch Meeting, John was always his affable self in the pub. I can honestly say I acquired a great deal from John Levy, which has helped me in my life as a lecturer in Wood Science over the past forty years - and it was not only the technical stuff that I learned from him! He was a wonderful person and is sorely missed.

James Coulson

Special thanks to John Ruddick and Harry Greaves for images:

Obituary

Written by Christopher Dodd in the Guardian, on Wednesday 28 September 2005

John Francis Levy, wood scientist, born June 30 1921; died August 11 2005

Influential wood scientist who was a keen coxswain despite having only one leg.

John Levy, who has died at 84, was a coxswain with a wooden leg who became Imperial College London's first professor of wood science. He spent the second world war coxing Imperial's crews on the Thames tideway while he was studying chemistry, botany and geology, his booming voice compensating for his limited stature and mobility. Later in his career he managed to marry his two passions, working on the 16th-century warship Mary Rose and experimental racing boat construction.

Levy was born in Brazil, at Morro Velho, near Belo Horizonte. He contracted polio when he was 18 months old, and immediately afterwards his mother brought him back to her family home of Cornwall, settling in Chapel Porth; and later moving to Tattenham Corner. Levy went to Ewell Castle school, and studied at Imperial College from 1939 to 1942. As a student his dream was to emulate Douglas Bader, the RAF pilot who flew after losing his legs. Levy had his withered left leg amputated and a false leg fitted. He would take the false leg off while coxing - sometimes leading to allegations of cheating by reducing his weight.

His first research project involved growing and studying tomatoes, a fruit which Levy couldn't abide, but he was soon diverted from his PhD studies in plant pathology (leaving his thesis unfinished) to lecture civil engineering students on timber and its properties in construction. He then spent 15 years teaching about timber and decay, establishing close cooperation with the Forest Products Research Laboratory.

His department was involved with others at Imperial in 1976 when the late Professor Alastair Cameron, of the lubrication laboratory, built an experimental, and highly successful, wooden racing four on the monocoque principle used in airframe construction. It won races at Henley powered by an Imperial crew, and prompted carbon fibre to be introduced into boat building by British Aerospace, which made an eight for the Olympic team. Monocoque construction became universal as wood bowed out as the favoured material for racing craft.

Levy was made a doctor of science and became professor of wood science in 1981. Initially encouraged by the British Wood Preservation Association, he started his research at Imperial's mine at Tywarnhale in Cornwall and at its field station at Silwood Park. This early work led to the establishment of a research group of worldwide renown, and it remains as his legacy. He also worked on the preservation of the hull of Mary Rose, and he studied the bows of the ship's archers, working out that the men must have been above average height to fire the deadly weapon.

He remained a rowing stalwart for his whole life as cox and then captain of Thames Rowing Club, Imperial's neighbour in Putney. Levy's presence in Imperial boats was keenly heard during the war when several college eights used the Thames regularly, often caught in air raids when they had to decide whether to run for shelter under a bridge or put distance between themselves and what may have been the Luftwaffe's prime target.

He served as president of both boat clubs and of Kingston regatta, and celebrated his birthday this year at Henley. Levy brought the same qualities of his professional life to his rowing activities, captaining Thames Rowing Club at the time when its committee outmanoeuvred its backwoodsmen to admit women as members. He was always quietly persuasive, never showing temper or raising his voice except when in the back of a boat.

His wife, Hazel, their sons Martin and Tim and daughters Jain and Wendy survive him.

This tribute was developed for inclusion wtih the March 2024 IRG newsletter.